Dr Michael Silverman of BioStrategics Consulting Ltd discusses some of the dilemmas associated with Phase 1 clinical study design and implementation in the field of oncology and the impact on drug development.

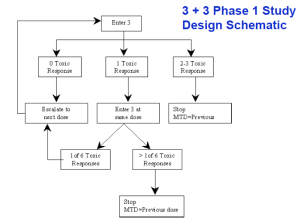

Many of you are knowledgeable about Phase 1 clinical trials in the field of oncology. For decades, the standard design has been the “3+3” trial (always in patients) to establish the safety profile, dose-limiting toxicity (DLT), and maximum tolerated dose (“MTD”) of a

new anti-cancer drug – and with good reason (J.Doroshow, NCI ). The design is time-tested and has numerous advantages, familiar to those of you with experience in the area. These advantages are compelling enough that the design has survived various proposals to alter the sample size and dose-escalation dynamics, the advent of “targeted” (ie, non-cytotoxic) cancer therapies, and various other challenges to its primacy.

The details of the design’s mechanics and advantages are beyond the scope of this blog, but I have found that the whenever a sponsor sits down and seriously considers an alternative, they always end up rejecting it in favor of the conventional design. One reason for this is that alternative designs generally use fewer patients, which decreases the information content of the trial and increases risk to the sponsor. Another, related, reason is the standard design encourages data-gathering and learning, so provides robust information about dose-relationship of adverse events and about pharmacokinetic behavior. In general, then, alternative or abbreviated designs seem more suited for known drugs in new settings, or for academic trials, than for new drugs being developed by commercial sponsors.

Having said that, the venerable 3+3 design is still capable of producing some surprises, even for those who have been through the drill many times. These “surprises” are counterintuitive in the sense that they are inherent in the design, but often not discussed, even by experts, in creating the clinical protocol. I’d like to briefly mention 3 dilemmas that this design can present to the sponsor, which can occur in any such trial but which may not have uniform or readily-applied answers.

Dilemma 1

The first relates to selection of the patient population, by which I mean the cell type of the primary tumor. There is very frequently a tension between choosing an “all-comers” design versus being highly selective in specifying one or a few tumor types. The former provides the advantages of easier recruitment and determination of MTD, while the latter may have solid rationale for certain targeted therapies based on nonclinical data, mechanism of action, and knowledge of the molecular pharmacology – all of which can, in theory, lead to an early demonstration of anti-cancer effect and proof-of-principle. The two approaches are not immediately reconcilable, thus leading to lengthy and repeated discussions in many early-stage programs. The best and most balanced approach I have seen to this conundrum has been to design an “all-comers” dose-escalation phase, followed by more selective enrollment in 1 or more parallel dose-confirmation cohorts.

Dilemma 2

A second dilemma relates to the decision process of cohort expansion following the first occurrence of a DLT at a given dose level. The usual “statute of limitations” for DLT declaration is 1 cycle (usually, 1 month or close to it), so what if there are still 1 or 2 patients who have not reached the end of Cycle 1? They are still at risk for first-cycle toxicity, and if one or both experiences a DLT, then that dose is declared to be above the MTD. Do you, as the sponsor or investigator, delay cohort expansion until the remaining patients reach the end of Cycle 1, thus deliberately slowing the trial enrollment? Or do you open the cohort expansion to 6 patients immediately, knowing that the dose may still be above the DLT and thus exposing the newest patients to unknown risk? It’s an interesting challenge that, depending on the unique situation may be answered either way, but most commonly I see – and often advocate for – the former decision, to ensure patient safety.

Dilemma 3

What should be done to the dose of patients who are tolerating what is now known to be a dose that exceeds the MTD? In other words, if 100 mg, say, is declared to be above the MTD based on the occurrence of DLTs in 2 patients, but anywhere up to 4 other patients are taking 100 mg without undue toxicity, should they be allowed to continue on this dose, on the theory that it’s not doing harm and may be doing good? Or should they immediately be dose-reduced to the MTD, on the theory that no patient should receive a dose that exceeds the MTD? I have had numerous conversations and debates about this, and have seen it go both ways. Generally, I’m more comfortable dose-reducing, and may even put it into a protocol or 2, but truth be told, my point of view does not always carry the day.

I would be delighted to hear your thoughts on these issues, your approaches, or anecdotes about other dilemmas you have faced in similar circumstances. To make comments or ask questions, click on this link.

For more information: go to www.biostrategics.com or send me an email at msilverman@biostrategics.com

Copyright © 2011 BioStrategics Consulting Ltd.